A Tale of Two Chapels

One of Seattle's earliest neighborhoods and its distant connection to Jack the Ripper

Much has been written about Pioneer Square and its previous history as Seattle’s so-called “red light” district. As the city grew in size towards the end of the nineteenth century, certain parts of this neighborhood became known for the abundance of brothels, gambling dens, and saloons. In the early days, this area of town was called Maynard-town after famous Seattle degenerate, Doc Maynard. It has also been known as Skid Road, the Badlands, the Deadline, and either the “Lava Beds” or “the Sawdust Pile” - both of which refer to the area of tide flats that were filled in with sawdust from the sawmill. When Seattle Police Chief Charles “Wappy” Wappenstein and Mayor Hiram Gill ran their extortion racket there in the 1910s, it was known as Wappyville.

Mostly, though, this district has been known as the Tenderloin - a term commonly used during the turn-of-the-century for those disreputable areas within a city known for their high crime rates, poverty, and vice. The name reportedly derived from the fact that cops patrolling such neighborhoods were able to afford the most expensive cuts of meat from all the payoff money they were collecting.

This neighborhood’s official boundary - otherwise known as the “deadline” - fluctuated over time due to various socio-economic factors, with Mill Street (now Yesler Way) generally serving as the line of demarcation between the business district to the north, and all the seamy vice establishments found to the south. In the early days, Seattle was divided into wards which formed the basis for representation in the City Council, and the Tenderloin was located in the working class “First Ward” which encompassed parts of what is now Pioneer Square, SoDo, and Georgetown.

In 1888, a particularly rowdy section of the First Ward became known as Whitechapel (also spelled White Chapel). This followed an early American tradition of naming neighborhoods in the new land for similar neighborhoods in the old world. In the case of Whitechapel, various neighborhoods started earning that moniker in honor of the high-crime and slum-like conditions of the infamous district in east London. This became even more macabrely popular after the gruesome Jack The Ripper killings in 1888, earning the impoverished London ghetto an elevated degree of worldwide notoriety. Newspaper articles from the late 1880s reference Whitechapel districts in Spokane and Everett, and Portland, Oregon’s Old Town neighborhood was also once known as Whitechapel due to its illicit reputation.

(Impoverished Whitechapel district in London, circa late 1880s)

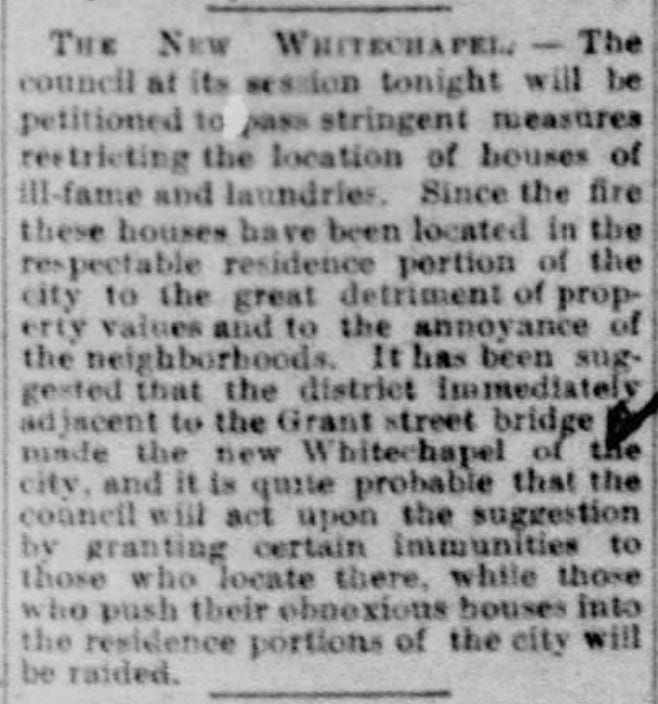

In 1889, the neighborhood was relocated as a result of the Great Seattle Fire. After the fire gutted most of the city, including the original Whitechapel district, various brothels and other vice establishments began sprouting up in surrounding residential neighborhoods, much to the chagrin of the more affluent residents who lived there. The matter became such an urgent concern that the City Council took up the matter a mere two weeks after the fire in which they proposed stringent measures to relocate all “the houses of ill-fame” which had been spreading throughout “the respectable residence portion of the city to the great detriment of property values and the annoyance of the neighborhoods.” It was therefore decided that “the district immediately adjacent to the Grant street bridge be made the new Whitechapel of the city.”

At the time, the long-since-demolished Grant Street Bridge was the primary thoroughfare to carry people over the Elliot Bay tidal flats, spanning from Jackson Street to what is now the SoDo district. And so, following all the post-fire rebuilding efforts that subsequently took place, a new Whitechapel district emerged. It was initially confined to a relatively small area spanning from Washington to King Street, between the 2nd and 3rd Avenue corridor. The boundaries for this new Whitechapel were not exactly static, as it would change over time, but it would always retain its semantic connotation to the infamous east London slums where Jack The Ripper murdered his unfortunate victims. Most importantly for city officials, though, it was an area of town where all manners of illicit behavior could be contained while they focused on rebuilding the city into a respectable destination.

By 1890, local papers were filled with rather poetic descriptions of the neighborhood, including a Tacoma News Tribune article titled, “Whitechapel, That City’s Seat of Sin and Shame,” which warned that “no better advertisement of lewdness, vileness, corruption and lawlessness, could have been selected by those without the pale of the law, without cleanliness, or righteousness, than this name, Whitechapel…The oily sneak, the crook, burglar, thug, and villain, willing to soil his hands for gain; the palsied, blear-eyed fiend of the opium habit; the gaudily bedecked brazen women of town go to make up for the population of the city’s fester spot and cancer - Whitechapel.” It continued its prose-like description of the Seattle district, ”Everywhere is crime and pollution, drunkenness and beastly debauchery. There is the brazen harlot, soliciting sin at the portals of her gaudy brothel. Here the fiend of the pipe, pale, trembling, a skeleton alive, hastening to his den to drown pain, perhaps remorse, with the deadly but soothing drug.”

Such colorful exposition only succeeded in establishing Whitechapel as an attractive destination for thrill-seekers looking for some illicit adventure and perhaps a night of fun with a “brazen harlot.” Such visitors were never left disappointed by the sheer number of vice dens in the neighborhood, including a wide selection of saloons: The Mirror, Tom Clancy’s, The Palace, Billy’s Mug, and The Never Touched Me. There were also several lively dance halls, many of which were technically illegal under Washington state law due to the so-called “barmaid law” which mandated that, “No female person should be employed in any capacity, in any saloon, beer hall, bar room, theater, or place of amusement where intoxicating liquors are sold as a beverage.” Needless to say, such rules were openly ignored in the Whitechapel, including one of the biggest dance halls at the time, The New Zealand, which employed several attractive female servers, making it one of the city’s top attractions.

Like moths to a flame, this smorgasbord of vice soon began attracting all manner of the criminal underworld, with one article remarking, “It was said that some of the most notorious pickpockets, bunco men, safe crackers, and murderers ever in the city were to be seen nightly in White Chapel.” Another newspaper observed, “The city is now infested with crooks, burglars, sneak thieves, and criminals of every degree as it has never been infested before.”

In addition to all the saloons and dance halls, the brothels in Whitechapel were never in scarce supply either. The most well-known of these bordellos was Lou Graham’s building on 3rd Avenue and Washington Street described as, "a discreet establishment for the silk-top-hat-and-frock-coat set to indulge in good drink, lively political discussions and, upstairs, ribald pleasures." Much has been written about Graham over the years - some of it fact, some of it fiction - but she remains one of the city’s more infamous historical figures and her building still stands today as the Union Gospel Mission.

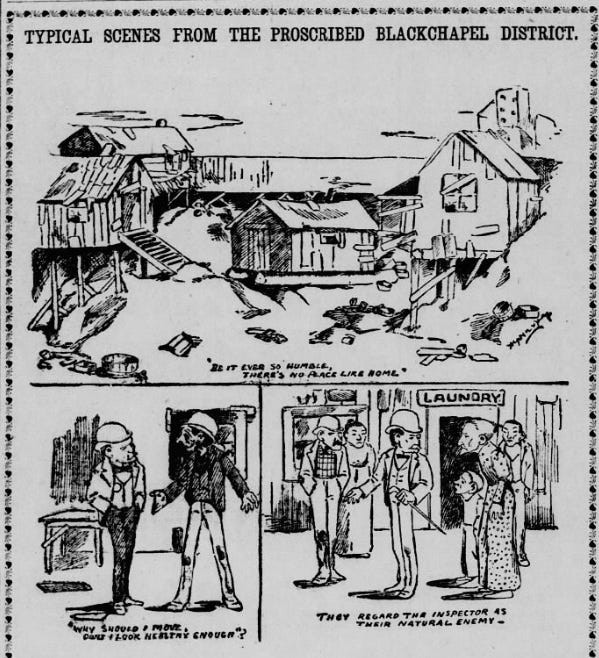

Soon after the emergence of Whitechapel, Seattle would welcome yet another “chapel” district. Situated in the tiny two-block expanse of 6th and 7th Avenue, between King and Weller streets, sat what became known as Black Chapel. The semantic origins of Black Chapel are unclear, though the record seems to indicate it was a tongue-in-cheek play of words to describe the literal filth, dirt, and stench that district was known for. In short, Black Chapel was the slums.

While neither district was viewed favorably, the local press seemed to reserve extra disdain towards Black Chapel, which was widely viewed as being the armpit of the city. “Men sleeping in doorways, doors padlocked for non-payment of rent, condemned buildings,” wrote one reporter, adding, “Its occupants are wharf rats and the riffraff of the slums. During the early evening they may be seen lounging in the filthy, ill-smelling beer saloons which are thick in the district…only the most depraved could ever seek such a place.” Yet another article described Black Chapel as “a veritable festering sore of inequity and licentiousness.”

(early Seattle newspaper strip lampooning the living conditions in the Black Chapel district)

Black Chapel also boasted a famous brothel. Located on King Street and 7th was the notorious Midway which reportedly offered the cheapest rates in town. It was written of the Midway that “there were girls of every race and color, ranging in age from seventeen to seventy. The small cubicles they occupied bore the names of the city or country they came from.” The Midway only operated for a couple of years before finally meeting its demise when a lumberjack from Snohomish county, who had reportedly been robbed by one of the girls working there, blew the Midway up with several sticks of dynamite.

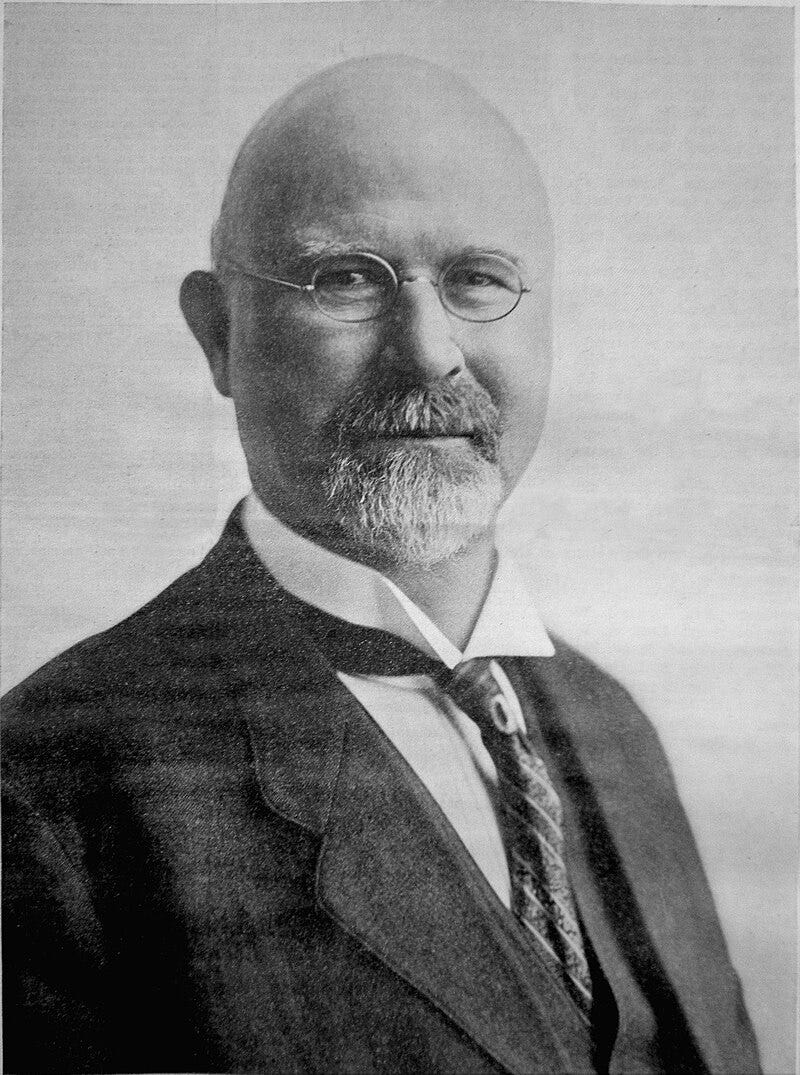

In 1892, Seattle Mayor J.T. Ronald worked tirelessly to shut these two districts down. While campaigning for office, he had promised that his first act would be to fire the chief of police, whom he believed was accepting kickbacks from Seattle's gambling halls and brothels. Ronald later wrote in a memoir that shortly after he was sworn in, the chief reportedly offered him a cut of the take and Ronald fired him on the spot. Ronald only served one two-year term, from 1892 to 1894, which he later described as the most unhappy years of his life.

(Seattle Mayor J.T. Ronald who led early efforts to close down the two Chapel districts)

His mission to rid the city of the two Chapel districts would prove to be an uphill battle, but in his words they were a “stench in the nostril of decency and a disgrace upon the good name of Seattle.” Not surprisingly, he targeted Black Chapel first, writing the following editorial in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

“The space bounded by South Sixth and South Seventh and by King and Weller streets is what is known as ‘Black Chapel.’ It contains numerous cribs and saloons, These cribs are occupied by a very disreputable element of the city. This stench upon the body politic, this black spot upon the escutcheon of the city cannot be wiped out if we allow and maintain so many saloons within so small an area. It is needless to say that many of these saloons are no reputable places. They ought not be allowed. I simply desire to put myself upon the record against allowing any more saloons in this Black Chapel district. Very respectfully yours, J.T. Ronald, mayor Seattle, Wash, Dec. 12, 1892”

Thanks to Ronald’s efforts, Black Chapel was temporarily “cleaned up,” but it wouldn’t be until seven years later, in 1899, when the Seattle Board of Health actually condemned Black Chapel, ordering all residents to vacate their houses on account of “unsanitary conditions,” at which point all buildings within the district were then demolished.

By the following year, in 1900, the term Whitechapel had gradually fallen out of favor. City planners and various officials were working hard to elevate the status of Seattle and boost its ranking as one of the top cities in America. Given these efforts, the idea of having one of the city’s top neighborhoods associated with the grisly Jack The Ripper killings had become increasingly unsavory and local newspapers were encouraged to begin re-using the much more appealing term, Tenderloin, when describing the district.

Over the next several years, various events such as the Jackson Street regrade project would prompt the boundaries of the Tenderloin to shift a bit. In 1902, the Tenderloin was relocated several blocks south in an effort to “open up valuable downtown land for other business and insulate respectable citizens from the vice trade.” As Seattle Mayor Thomas J. Humes announced, “I have instructed the detectives to notify the women in the crib houses to prepare to move south as fast as quarters can be obtained for them. It is not my purpose to work a hardship on anybody, but it will be my policy to move the women of this class out of the wholesale and jobbing district between Yesler Way and Jackson Street.” According to one article, several hundred women were affected by this.

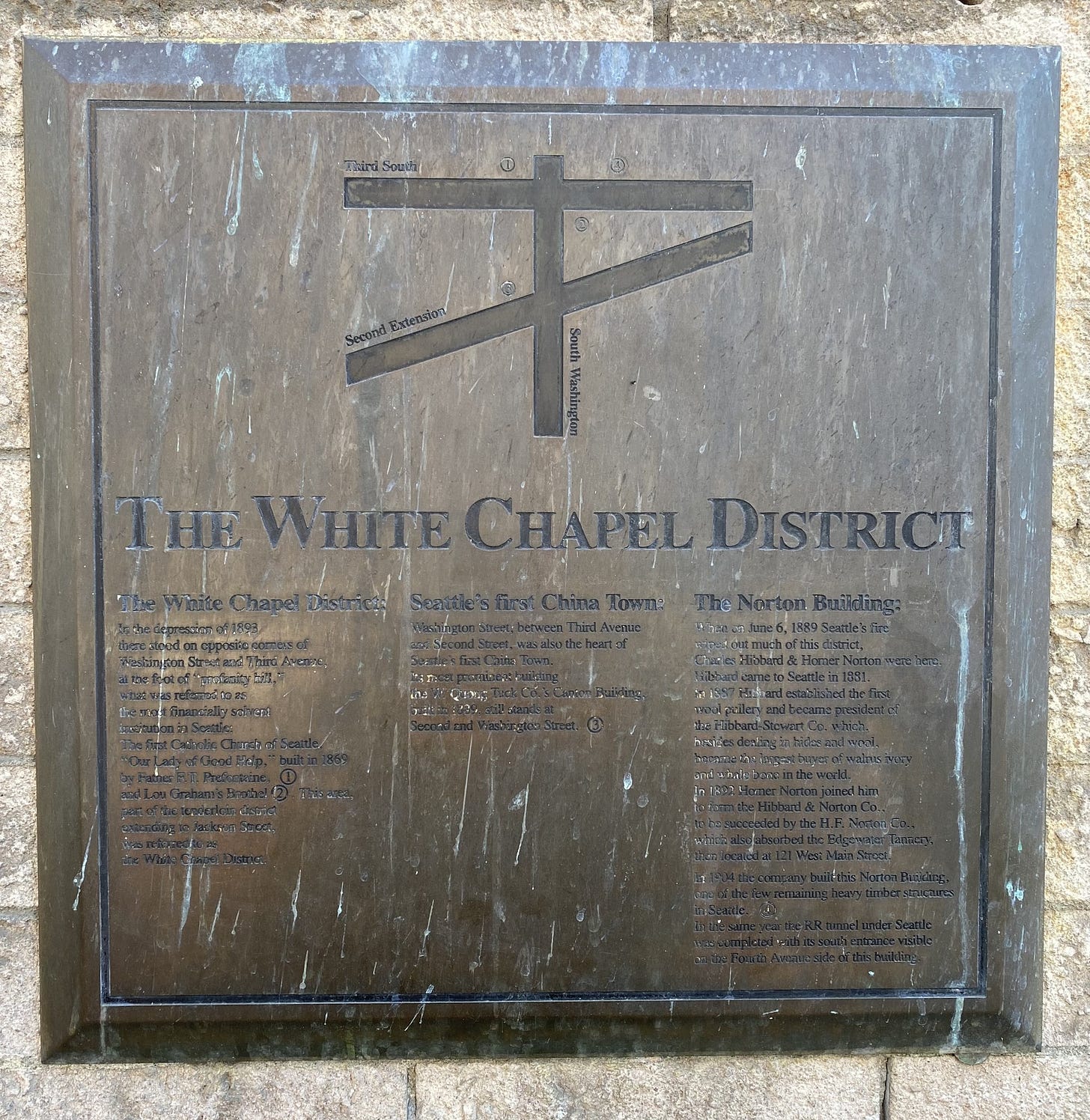

It wouldn’t be until the Prohibition era that many of the neighborhood's vice establishments would be finally chased away for good, though the infamy of that district is still celebrated to this day. An historic plaque located at 3rd and Washington commemorates the White Chapel district though, unsurprisingly, there is nothing to memorialize the long forgotten slums of Black Chapel.

Wow. It is funny how people took the names of the old country and applied them to American places. I like how there was White Chapel and Black Chapel, like two competing camps. It sounds like an old Western where a guy with no name comes in and tries turn one against the...anyway, ha. I wonder if the writer Tom Clancy was aware that one of the places shared his name. I guess JT Reagan had a heck of a time, but it sounds like he did some good work there. It must have been a very stressful job indeed. This is a wonderful article, Brad. Awesome job.