Night after night, the darkness of the evening sky was illuminated by yellow flames - sometimes hundreds of feet high – as the city’s warehouses, factories and buildings were set ablaze by an unknown assailant. Each new smoldering building would fill the air with the increasingly familiar smell of acrid smoke, often lingering for days afterwards. For the Seattle Fire Department, the situation was becoming an exhausting nightmare that never seemed to stop. They would often respond to one fire when a new alarm would suddenly be sounded for another. Their top investigators were joined by seasoned detectives in an effort to catch the person responsible, though no amount of police work seemed to turn up any solid leads. The entire city was on edge. There would eventually be a high-profile arrest, but not before some of Seattle’s most prized landmarks were destroyed by an unfettered pyromaniac who terrorized the city for four long years.

The first confirmed arson took place on the evening of March 19, 1931, at a three-story building occupied by the Art Woodworking Company, near what is now T-Mobile Park. Firemen valiantly fought the blaze for well over an hour but all such efforts proved to be futile as the business was packed full of incendiary varnish and paint. It would be described as a “spectacular fire of undetermined origin.”

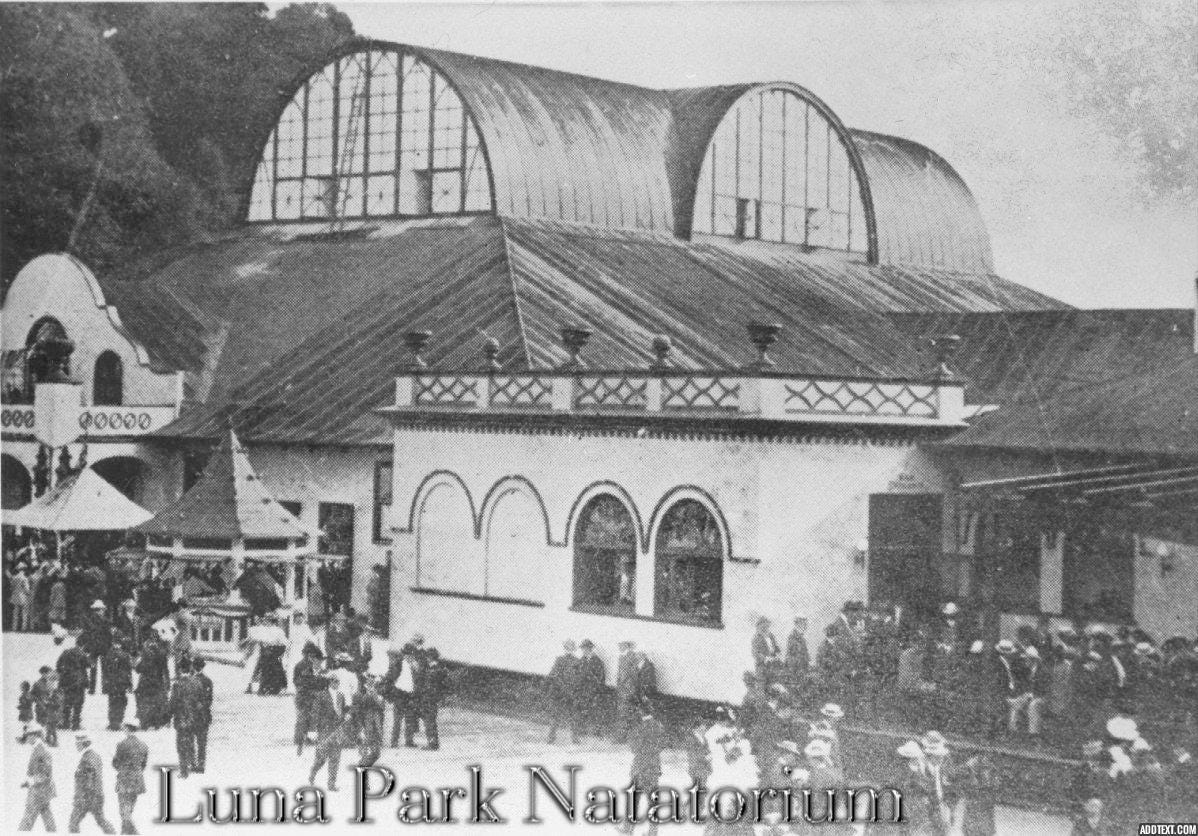

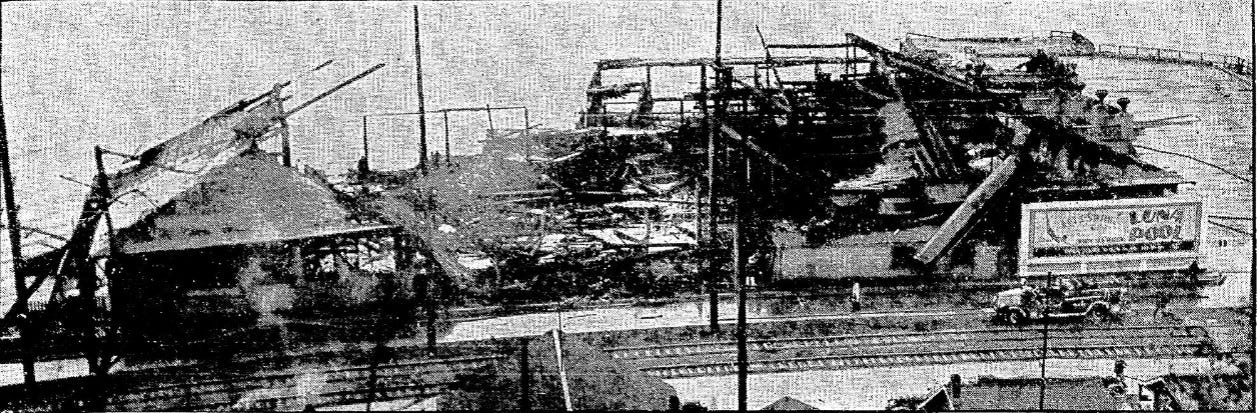

Two months later, a total of nine different fire stations would find themselves urgently responding to an early-morning alarm at the Luna Park Natatorium. Described as a “swimming palace,” the West Seattle landmark was the last remaining structure leftover from the famous Luna Park Amusement Park. The prominent building, which stood on a broad wooden pier, featured two heated pools and was one of the city’s most popular attractions.

The fire alarm at the Natatorium was first sounded at 3:46 am, and within an hour the flames were so high that they could be seen from the other side of Elliot Bay. Many local residents watched the historic blaze from Queen Anne and Beacon Hill. In addition to the large battalion of firetrucks, two fire boats were also deployed to help douse the flames. Despite such a large-scale response, the building – including the pier it was housed on – was completely destroyed. The entire structure would later be declared a total loss and the city would officially condemn the property in 1933, after rebuilding costs were deemed to be too expensive.

Over the next fifteen months, several other buildings would meet the same fiery fate: the Albers Flour Mill, Ace Iron Works, the Globe Feed Mill, and the Erhlich-Harrison Lumber Yard. Schools, churches and private residences were also hit, and it soon became apparent to most residents what investigators were already well aware of, which was that Seattle was dealing with its first serial arsonist.

Longtime fire inspector, R.L. Laing was eventually assigned to the case. Laing was a tough-as-nails, no-nonsense investigator who was described by colleagues as “untiring and relentless.” He had a known track record for hunting down and prosecuting arsonists, though this would prove to be one of the most difficult cases of his career.

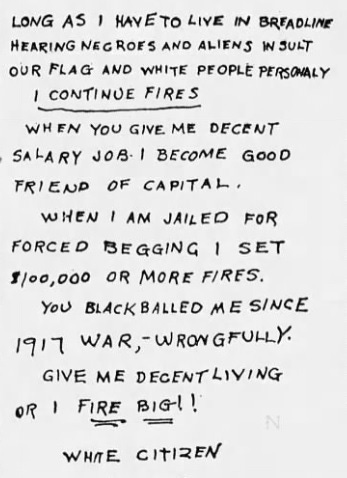

Soon after his appointment, things took a curious turn when a small fleet of fire engines responded to yet another alarm. Expecting to find a blazing fire, they were somewhat relieved to discover that it had been a false alarm. However, a hand-written note had been attached to the alarm box, intentionally left for the firemen to discover. It read in part:

“LOOK OUT! So long as I am blackballed for not being in the last war I will continue many fires in industrial plants. FIREBUG ALL OVER COAST.”

Another note soon followed which contained racist language and identified the author as being a “white citizen.” The first world war was again referenced:

“You blackballed me since

1917 war–wrongfully.

Give me decent living

Or I fire big”

At first glance, the grammar and handwriting appeared to be rather crude and from someone with a low level of education. Right away, though, Inspector Laing suspected subterfuge. He consulted with a local detective – a handwriting expert – who closely examined the letter and affirmed Laing’s theory. Much of the writing was cramped and unnatural looking, though some of the letters were nicely formed, as though the person had slipped and accidentally revealed their true writing in certain parts. “It’s a disguise,” the detective told Laing, “You’re dealing with a smart man. I would guess that the man who wrote this was a bookkeeper or stenographer at one point.”

By spring of 1932, the fires had become a nightly occurrence. The Blackstock Lumber Company, The Stewart Electric Company, The Eyres Transfer Company, the Bayside Garage - all reduced to ruins. Special police units aggressively patrolled the streets, and watchmen were secretly stationed throughout the city. Anyone looking suspicious or caught walking alone at night were stopped and asked to explain their business. Hundreds of people were questioned to no avail.

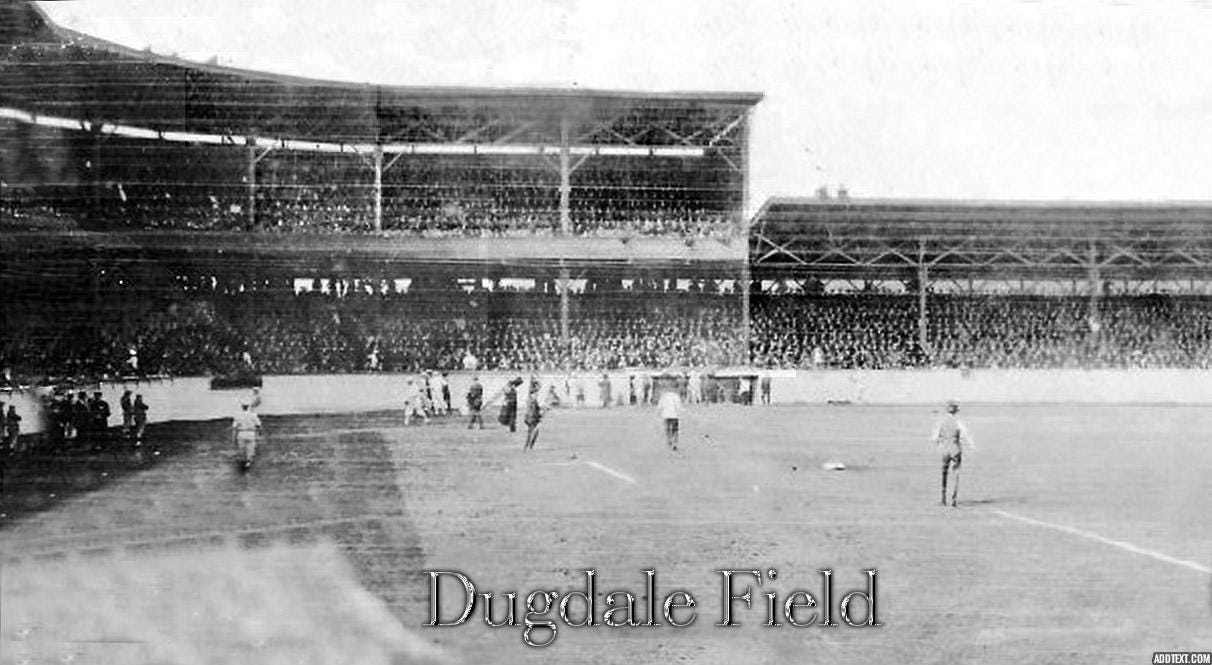

Despite the constant threat of fire, local residents attempted to lead as normal lives as possible. This included the cherished pastime of baseball. On July 4, 1932, a packed house at Dugdale Field watched the Seattle Indians play a doubleheader, followed by a traditional Independence Day fireworks show. Shortly after midnight, when the 15,000-seat stadium was empty of fans and all gates had been securely locked up, calls started urgently pouring in that the 19-year-old ballpark was on fire.

The first responders to arrive found that much of the grandstands were already engulfed in flames and the scene was immediately declared a three-alarm fire. It was a colossal firefighting effort, made worse by a brisk wind which blew across the play field, fanning the flames and sending hot embers up into the air. Hundreds of nearby residents, alerted by the inferno’s massive glow and the continuous wail of sirens, packed into nearby streets to helplessly watch the incineration of their beloved ballpark. Many were said to be in tears.

By sunrise, all that remained of Dugdale Field was a charred tower of outdoor lighting that was somehow still in working order. The rest of the park had burnt down into a smoldering pile of rubble. It would later be described as one of the most spectacular blazes in the city’s history. Initially, the previous night’s fireworks show was thought to be the likely culprit. It wouldn’t be until three years later, in a police interrogation room, that a late-night confession would reveal it to have been an act of arson.

Soon after Dugdale Field burned down, the fires mysteriously stopped. Days of no arsons turned into weeks, which then turned into months. Local officials grew cautiously optimistic that the firebug had finally left town, and all special patrols were slowly withdrawn from the streets.

Unfortunately, the fires returned six months later, starting in January 1935. Inspectors immediately knew it was their guy as the same fire-starting methods were being used on the same types of buildings. The first to be burned down was the Eastlake Lumber Company, followed by the Yeaman Brothers Mill. It eventually became a nightly routine, with building after building being lost to fire. Inspector Laing dutifully attended every suspected arson, hoping to gather evidence that could finally break the case.

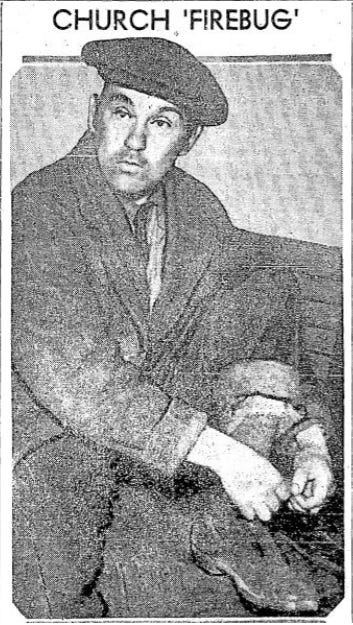

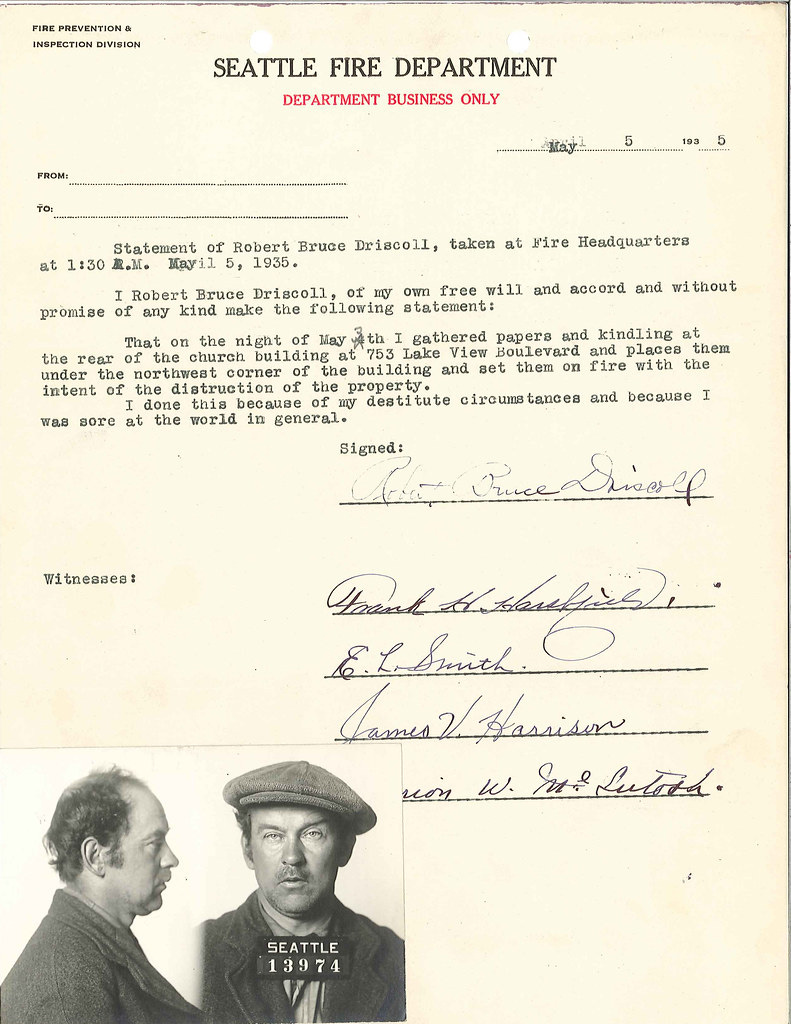

Everything would finally come to an end on the evening of May 4, 1935, when someone set fire to the Saint Spiridon Russian Orthodox Church, on Lakeview Boulevard. Nearby cafe workers, alerted by the frantic barking of a dog, spotted a shadowy figure fleeing from the scene and gave chase. They managed to detain the person, who was described as being dirty and unkempt. When police arrived, he identified himself as Robert Driscoll.

The suspect was promptly driven to police headquarters for further questioning. At first, Driscoll was steadfast in his denial about setting any fires. After a couple days of interrogation, though, certain biographical details began to surface. It was revealed that he was a 43-year-old vagrant who frequented the city’s breadlines and soup kitchens, and usually found shelter in abandoned railroad cars. As far as his background, he confirmed that he was college educated and had previously worked as an accountant. His MO certainly matched the profile, though police were still unable to obtain a confession.

At long last, Inspector Laing finally had his turn in the interrogation room. One of the first things Laing did was obtain a handwriting sample from Driscoll, and as suspected, it closely matched the writing from the notes. When confronted about this, Driscoll finally broke down and confessed to being the arsonist. He revealed that his anger at society began during World War I, when he had been drafted into the U.S. Army, despite being a conscientious objector. Following his military discharge, his house was foreclosed on. Afterwards, he found himself indignant, bitter and homeless. He told police that he hated the “bosses and capitalists” and “wanted to show them they couldn’t push me around.” Summarizing his Holden Caulfield-eque outlook on life, he stated, “I was sour on the world and broke. I just wanted to destroy anything - it didn’t make any difference to me.”

In 1935, Driscoll was given a 10-year sentence at Walla Walla State Penitentiary. Inspector Laing, who would later serve as the city’s Fire Chief, paid Dricoll a few visits at the prison, perhaps to gain some useful psychological insights into what motivated such a person. Driscoll was said to be unremorseful and promised more arsons if they ever let him out. ”I’m crazy about fires,” he exclaimed, “I guess if I was out tomorrow I’d start some more fires. It’s better that I’m here.” Perhaps to the world’s benefit, Driscoll never had the chance to test such impulses as he reportedly died during his incarceration. Current estimates hold him responsible for over 175 fires.

Since his death, Driscoll has become a rather interesting footnote in local sports history. After the torching of Dugdale Park in 1932, the Seattle Indians were forced to relocate to a lesser-quality playing field in lower Queen Anne. This new venue never worked for the Indians, especially during the height of the Great Depression. By 1937, the team was on the verge of bankruptcy and ended up being sold to local brewery magnate, Emil Sick, who rebuilt Dugdale Field into a concrete and steel ballpark known as Sick’s Seattle Stadium and introduced the city to its new minor league baseball team, the Seattle Rainiers. The stadium put Seattle into a position to acquire its first major league franchise, the Seattle Pilots, which later led to the Mariners. In short, Seattle may have never acquired a major league baseball team if Dugdale Field hadn’t burned down. While this surely wasn’t Driscoll’s intended outcome, there is a certain irony to the fact that his attack on the country’s favorite pastime, on the most patriotic of days, was all because of an unfulfilled American dream.