May 21, 1922

It was a dark and drizzly spring morning when a call came into the Edmonds Independent Telephone Exchange. Lillian Bartlett, one of the younger switchboard operators working there at the time, answered in her customary greeting, “Hello, operator.”

A female’s voice responded though her words were quite slurred, making it difficult to understand much of what she was saying. This was becoming an increasingly common problem for the “Hello Girls” of the Prohibition era. Lillian was able to decipher enough to understand that the woman wanted to speak to Bob Farley at the White Horse Tavern. Like many local residents at the time, Lillian was quite aware of the notorious roadhouse as well as its equally-notorious owner, so she knew precisely which number needed to be connected on the switchboard.

”Hold the line, please,” she instructed while plugging the cable into the proper jack. A man’s voice soon answered and the two parties began talking. Ordinarily, operators were required to disconnect from the call once it was patched through, but occasionally…just occasionally…they might linger on the line for a bit. It was a fireable offense to do so, but boredom and the temptation of hearing some juicy town gossip often overrode such company policy. In this case, a drunk woman was calling the rowdiest establishment in town and Lillian’s curiosity got the best of her.

Less than a minute into the conversation, though, Lillian’s face suddenly went pale white and she put her hand over her mouth to stifle a gasp. The operator next to her noticed her reaction and after the call ended Lillian recounted the conversation in a hushed but excited tone while her co-worker listened on with wide-eyed astonishment. Within days the two operators would find themselves catapulted into the middle of a sensational news story.

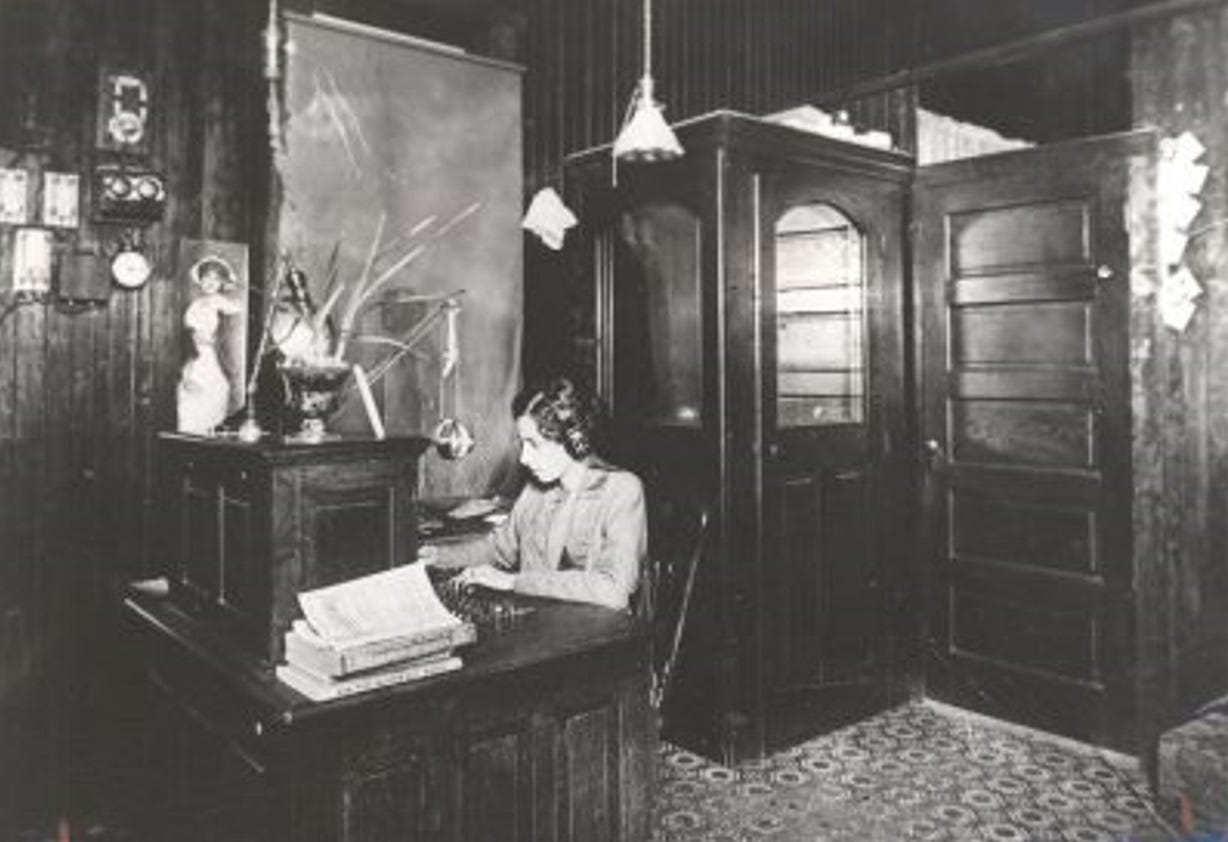

(Edmonds Independent Telephone Exchange)

Based on official police records, the events leading up to that fateful call were as follows: at approximately 2:30 a.m., a man - later identified as Westley Howarth - had been mysteriously dropped off at Providence Hospital with a severe gunshot wound to the chest. He was in critical condition and smelled strongly of alcohol. His initial story to hospital staff was that his injury had been self-inflicted though he later reported that his girlfriend had actually shot him during an argument and was able to provide an address where it happened. Despite receiving urgent medical care, efforts to save Westley were unsuccessful. His time of death was listed as 3:46 a.m.

The police were immediately notified and two patrolmen were quickly dispatched to the Metropole Hotel - a rooming house in downtown Seattle. Upon their arrival they found three individuals inside, all of whom appeared to be fairly intoxicated. The scent of gunpowder still lingered in the air, puddles of blood spotted the floor, and officers made note that the revolver likely used in the shooting was casually sitting on a table.

One by one, the three suspects were questioned. First up was the deceased man’s mistress, Olga Farley, who told police that Wesley (who, it should be noted, was married to another woman at the time) had accidentally shot himself in a drunken stupor. One of the other party guests provided a different account, telling police that Olga and Westley had begun quarreling which, matching the pace of their drinking, only intensified throughout the evening. At some point they disappeared into a bedroom and around 2 a.m. the guests heard something being said about a gun in Olga’s purse, followed by a loud gunshot. Afterwards, a taxi was urgently called and a heavily-bleeding Westley was transported to the hospital. According to both guests, it was Olga who had fired the shot.

Olga was immediately placed under arrest and everyone was brought down to the station. While waiting to be questioned by detectives Olga requested to use the phone, where she then called into the Edmonds Telephone Exchange. As was noted by officers, Olga spoke to her ex-husband, Bob Farley, who was quite familiar to local law enforcement as he ran the White Horse Tavern - a well-known Edmonds roadhouse that had been the site of countless police raids as well as the subject of several titillating newspaper headlines. After hanging up the phone, Olga’s demeanor suddenly changed and she immediately requested an attorney.

Meanwhile, Lillian remained preoccupied with the call, but did her best to maintain a normal composure and finish out her shift. She and her co-worker anxiously debated back and forth about what to do, knowing very well that they could both possibly lose their jobs if the call was ever reported. For now, they decided to keep everything between themselves. Between calls, Lillian took a moment to lean back and take a quick look around the telephone business, nostalgically recalling her time there...

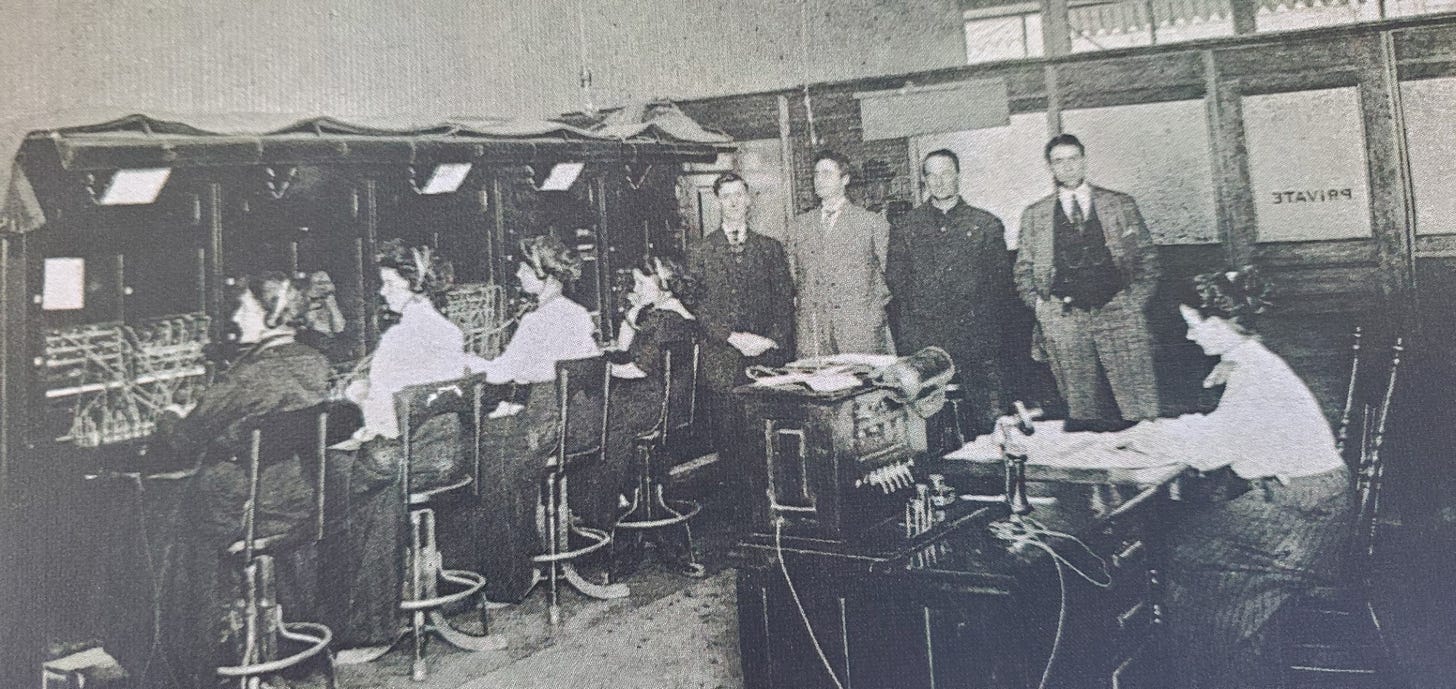

The Edmonds Independent Telephone Company was a small-town operation that ran out of a one-story wood building on Main Street. Answering the phones were a staff of “Hello Girls” – a term coined during World War I that referred to female telephone switchboard operators. During the Great War, several hundred Hello Girls worked for the U.S. Army Signal Corps, helping to improve communications on the Western front. The operators at the Edmonds exchange, which provided 24-hour phone service, were expected to be “courteous, quick-thinking and patient under pressure.” They worked in round-the-clock shifts, with Lillian and her co-worker part of the early morning team.

The following day it was announced that the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s office had filed second-degree murder charges against Olga Farley, with one of her party guest charged with aiding and abetting. While preparing for the case, a deputy attorney was dispatched to the Edmonds Telephone Exchange to learn more about Olga’s phone call. He arrived early in the morning, while Lillian was still on duty, and after identifying himself he asked to speak to the superintendent of the phone company, Daniel Yost. Daniel was the son of Edmonds businessman, Allen M. Yost – a local lumber and shingle magnate and former town mayor. Daniel immediately invited the attorney into his office and moments later a panic-stricken Lillian was asked to join them. The deputy attorney introduced himself and explained why he was there. The air felt thick and somewhat stifling, and Lillian’s heart beat so rapidly that she was worried that others could hear it. Picking up a notebook and pencil, the deputy attorney studied Lillian for a minute and then began his line of questioning.

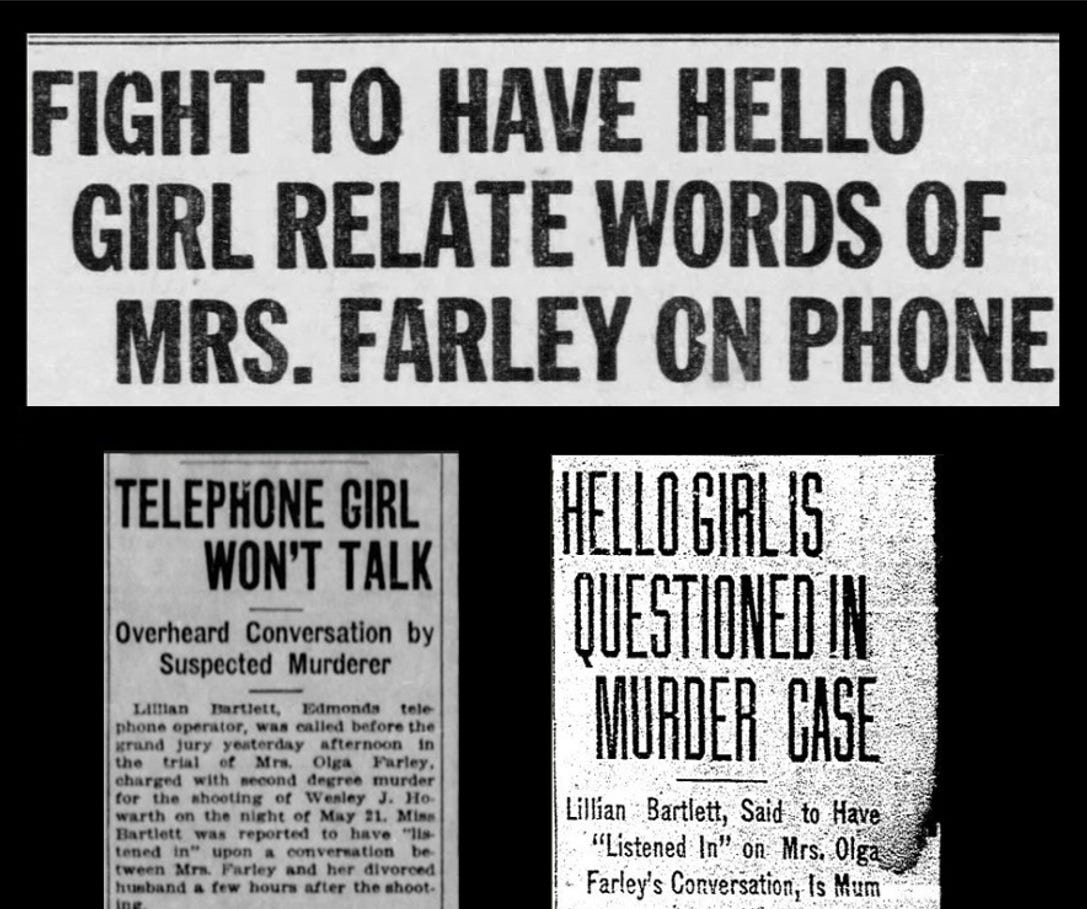

It did not take long for everything to come spilling out. A somewhat-relieved Lillian admitted to listening in on the conversation but as soon as she was about to recall what she had overheard, superintendent Yost suddenly stood up and demanded that the interview be terminated. The last thing he wanted was word getting out that operators at his telephone exchange were listening in on customer’s phone calls. The deputy attorney sternly reminded them about the severity of the crime that had been committed, as well as the seriousness of the investigation, but Yost stood firm in his refusal to permit any further questioning. Afterwards, several high-level discussions took place between Yost and higher-ups at their parent company, Pacific Telephone and Telegraph, and Lillian was firmly reminded to remain silent about anything she may have overheard.

(Operators at the Edmonds Telephone Exchange, 1921)

On June 2, 1922 - twelve days after the fatal shooting - the telephone exchange received a subpoena from the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s office seeking Lillian’s testimony before a grand jury. Acting on orders from her superiors, and not wanting to lose her job, she refused to comply with the court order. In response, a bench warrant was issued for her arrest. The following day, Snohomish County Sheriff W.W. West arrived at the telephone exchange and placed Lillian under arrest, where she was then transported to the King County Jail. She had never imagined herself ever being in such a nightmarish situation and wished over and over again that she had simply disconnected from that horrible call.

The next day Lillian was escorted to a nearby courthouse where the grand jury awaited her testimony. Joining her in the courtroom that day was the co-worker whom Lillian had confided in. A defense attorney, hired by the telephone firm, represented both women and argued against forcing their testimony, contending that, “Whatever was said on the telephone was confidential in the first place and, again, how can she positively identify the talkers? She did not see them. She is unable to say beyond question of doubt that it was Mrs. Farley and her divorced husband talking.” Superintendent Yost was also present and argued that the state had no right to require a telephone operator to disclose any information gleaned while “listening in.”

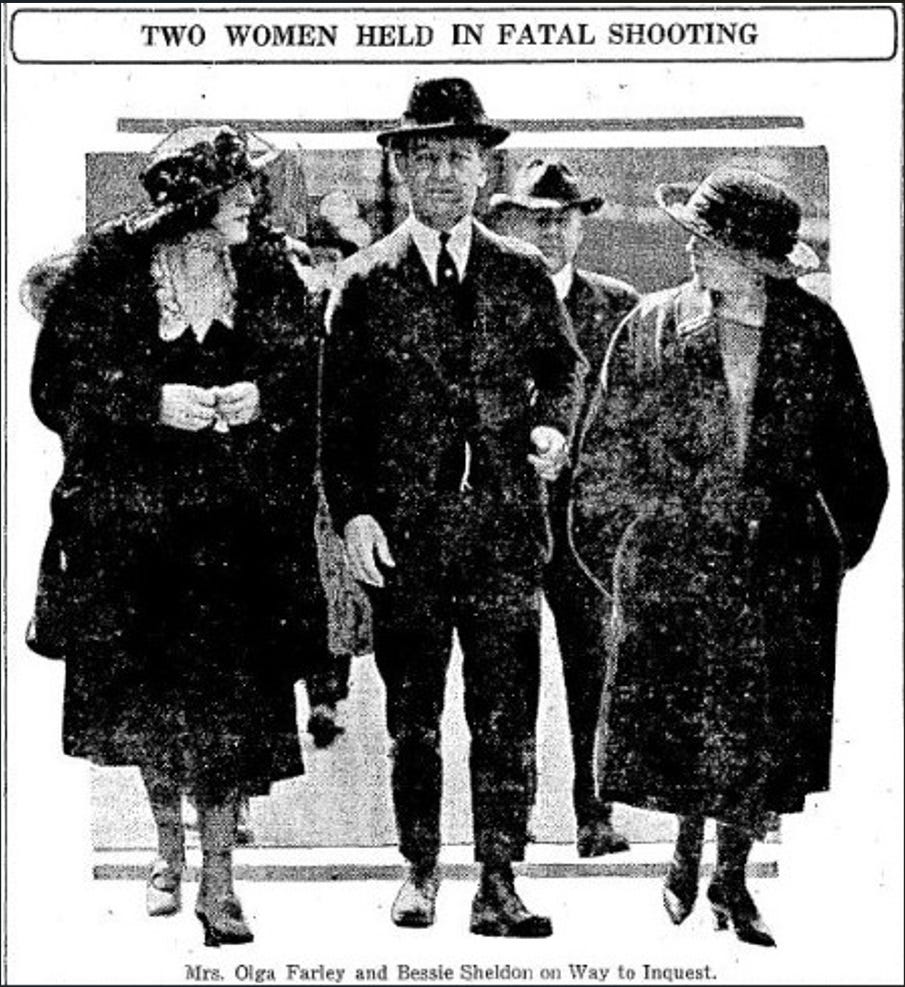

Despite such strong protests, the judge ordered both women to take the stand. What they divulged to the grand jury remains unknown, though it should be noted that Olga was quickly indicted on murder charges soon after their testimony. In the subsequent trial that would take place three months later, Olga’s defense attorney would maintain that Westley’s death was accidental. By this time, the whole story had turned into a rather ghoulish cause célèbre with the local papers often going out of their way to make note of Olga’s beauty. She was often described as a “vamp,” with one article gushing, “she is tall and slender, with sparkling blue eyes and rosy cheeks and lips that need no rouge.” Ultimately, the jury believed Olga’s convincing testimony that Westley had grabbed the revolver from her purse and that it had accidentally discharged when she struggled to get it back from him. The jury deliberated for less than an hour before finding her not guilty. The trial would become noteworthy in that it was one of the first examples of phone communications being used in a court case, testing the legal limits of privacy rights and confidentiality laws.

After the acquittal, Lillian was reportedly let go from the telephone exchange due to her unauthorized eavesdropping. The following year, though, in 1923, the Everett Herald would announce that Lillian had opened a new beauty parlor in downtown Edmonds. Operating out of the Princess Theater building, her new salon was noteworthy in that it represented one of the town’s first female-owned businesses. Olga, meanwhile, would stay true to her notoriety, later becoming the so-called “Queen of the Honolulu Underworld,” when it was reported that she had been arrested for operating several different prostitution rings throughout the Hawaiian Islands. Only this time she would not escape the charges, receiving a 5-year prison sentence. Olga’s ex-husband, Bob Farley, who ran the White Horse Tavern (later known as the historic Rosewood Manor), would also serve time in prison after shooting another man in Yakima following an 8-hour dice game in which he had reportedly lost money.

As for the Edmonds Independent Telephone Company, the original wood building would later be replaced with a concrete building and the business would continue operating well into the early 1940s. The building still stands today at 535 Main Street with an historic marker out front telling the story of the former telephone business though, curiously, no mention is made of that infamous phone call involving the Seattle “vamp” and the Edmonds “Hello Girl.”